Steps to Make Your Teaching Practice More Equitable

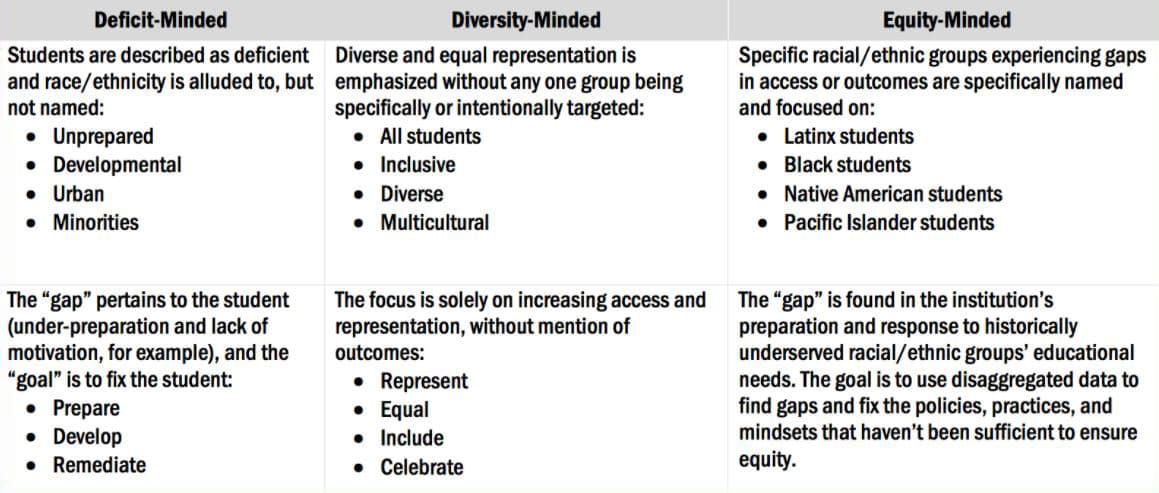

Research shows that many college instructors and practitioners can possess deficit-minded views about their students—meaning that signs of struggle are attributed to students’ lack of academic skills and preparedness. These deficit-minded views are often applied to historically-marginalized students (e.g., Black, Latina/o/x, low-income).

While it is important for educators to identify and address students’ lack of academic skills, a deficit-minded approach can position educators to mainly look at the students and their backgrounds as reasons for students’ academic shortcomings. In essence, deficit-mindedness blames the students for their struggles and can fail to provide educators the agency to do something about it.

In response, contemporary research indicates educators who shift to an equity mindset are able to identify teaching practices and institutional policies that contribute to inequities. This cognitive shift, enables educators to make changes to their own teaching practices and advocate for more equitable policies. In essence, equity-mindedness can build educators’ capabilities to address educational inequities.

Below, you’ll find a chart briefly describing the three cognitive frames that mainly focuses on students’ experiences (deficit- and diversity-mindedness) and the cognitive frame that places more emphasis on the agency of educators and administrators (equity-mindedness) (Center for Urban Education, 2020).

Another important step for making your teaching more equitable relates to your curriculum. Historically-marginalized college students can feel disengaged in the classroom because the “traditional” curriculum does not reflect students’ personal or professional lives. When students do not see themselves in the curriculum, they may fail to gain the knowledge and skills to understand themselves, their community, and/or future profession.

To address this, college educators can include content highlighting how marginalized people have contributed to the knowledge of a given area of study. For example, communication instructors can include the story of Ida B. Wells—the prominent Black journalist who shed light on Black Americans post-Civil War.

Educators can also have students connect their lived experiences to the course content. This can be done with short written assignments in which students apply the terms and ideas from the course to their personal and/or professional lives. This high order of thinking can enable students to recognize their knowledge as valuable, and identify and ratify misconceptions. In this sense, students’ lives become part of the curriculum.

These are only two ways to add content that is relevant to students’ lived experiences.

More info on asset-based teaching (Culturally Relevant, Responsive, and Sustaining Pedagogies).

Along with the curriculum, instructors interested in being more equitable should consider

how their instructional practices are impacting students. Research shows historically-marginalized

students do exceptionally well when they are able to actively engage with the coursework.

Active learning is defined as a broad range of teaching strategies which engage students

as active participants in their learning during class time with their instructor.

According to the Center for Teaching & Learning at the University of Minnesota, there

are several fundamental components of active learning strategies:

Talking & listening:

Students actively process information when they ask or answer questions, comment, present, and explain. Discussions and Interactive Lectures are useful strategies.

Writing:

Reflective writing can help students organize their thoughts and prepare them for discussion. Check out these suggestions for Informal Writing Activities .

Reading:

Transform reading into an active process by providing students with questions and summary exercises.

Perusall for active annotations

Reflecting:

Reflecting on the applications and implications of new knowledge can help develop higher-order thinking skills.

View a reflective process that can produce meaningful learning outcomes

Critically-reflective Educator

A critically-reflective educator means you examine how your teaching practices are impacting all your students—particularly those who come from marginalized communities. Then, you can make changes to your teaching practices to better ensure your teaching is accessible to all of your students.

Given that Albertus serves a relatively high percentage of Black, Latino/a/x, low-income and first-generation college students, it is crucial for the Albertus faculty to develop a routine in which they continuously reflect on their teaching and recognize when changes are needed in order to maximize the potential of our students. This reflective process can happen on your own, in workshops and/or through conversations with peers.

Regardless of your reflective approach, there are sets of questions you want to ask yourself in order to understand your teaching strengths and areas of improvement. Below, you’ll find two documents that provide some guidance on practicing critical reflection.

Guide with reflection questions you can answer

Tool to self assess your teaching and map out potential changes

- Almaguer, T. (2012). Race, racialization, and Latino populations in the United States. In D. M. HoSang, O. LaBennett, & L. Pulido (Eds.), Racial formation in the twenty-first century (pp. 143-161). University of California Press.

- Anderson, M. (2016, July). Blacks with college experience more likely to say they faced discrimination. http://www.pewresearch.org/facttank/2016/07/27/blacks-with-college-experience-more-likely-to-say-theyfaced-discrimination/.

- Bell, D. (1992). Faces at the bottom of the well: The permanence of racism. Basic Books.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (1997). Rethinking racism: Toward a structural interpretation. American Sociological Review, 62 (3), 465-480.

- Brayboy, B. M. J., Fann, A. J., Castagno, A. E., & Solyom, J. A. (2012). Postsecondary education for American Indian and Alaska Natives: Higher education for nation building and self-determination. Jossey-Bass.

- Garcia, G. (2017). Defined by outcomes or culture? Constructing an organizational identity for Hispanic-serving institutions. American Educational Research Journal, 54 (Supplement 1), 111S-134S.

- Ginder, S. A., Kelly-Reid, J. E., & Mann, F. B. (2016). Postsecondary institutions and cost of attendance in 2015-2016; degrees and other awards conferred, 2014-2015; and 12-month enrollment, 2014-2015: First look (preliminary data). (NCES 2016-112). http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2016/2016112.pdf.

- Glenn, E. N. (2002). Unequal freedom: How race and gender shaped American citizenship and labor. Harvard University Press.

- Godsil, R. D., Tropp, L. R., Goff, P. A., & Powell, J. A. (2014, November). The science of equality, volume 1: Addressing implicit bias, racial anxiety, and stereotype threat in education and healthcare.http://perception.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Science-of-Equality.pdf.

- Guillory, R. M., & Wolverton, M. (2008). It’s about family: Native American student persistence in higher education. The Journal of Higher Education , 79 (1), 58-87.

- Harper, S. R. (2012). Race without racism: How higher education researchers minimize racist institutional norms. The Review of Higher Education, 36 (1), 9–29.

- Harper, S. R., Patton, L. D., & Wooden, O. S. (2009). Access and equity for African American students in higher education: A critical race historical analysis of policy efforts. The Journal of Higher Education, 80(4), 389-414.

- Hispanic Association of Colleges & Universities (2016). 2016 fact sheet: Hispanic higher education and HSIs. Retrieved from http://www.hacu.net/hacu/HSI_Fact_Sheet.asp.

- Museus, S. D. (2014). Asian American students in higher education . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Museus, S. D., & Kiang, P. N. (2009). Deconstructing the model minority myth and how it contributes to the invisible minority reality in higher education research. New Directions for Institutional Research, 142 , 5-15.

- Museus, S. D., Ledesma, M. C., & Parker, T. L. (2015). Racism and racial equity in higher education. ASHE Higher Education Report , 42 (1). doi: 10.1002/aehe.20067.

- Nguyen, B. M. D., Nguyen, M. H., Chan, J., & Teranishi, R. T. (2016). The racialized experiences of Asian American and Pacific Islander students: An examination of campus racial climate at the University of California, Los Angeles . http://care.igeucla.org/wpcontent/uploads/2016/05/2016_CARE_Report.pdf.

- Nguyen, B. M. D., Nguyen, M. H., Teranishi, R. T., & Hune, S. (2015). The hidden academic opportunity gaps among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: What disaggregated data reveals in Washington state. http://care.igeucla.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/iCount-Report_TheHidden-Academic-Opportunity-Gaps_2015.pdf.

- Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. G. (2001). Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. University of California Press.

- Proudfit, J., & Gregor, T. (2014). The state of American Indian & Alaskan Native education in California. https://www.calstate.edu/externalrelations/documents/CICSC-2014-Education-Report.pdf.

- Rusin, S., Zong, J., & Batalova, J. (2015, April). Cuban immigrants in the United States. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/cubanimmigrants-united-states.

- Santiago, D. (2015). The condition of Latinos in education: 2015 factbook. Excelencia in Education.

- Smith, W. A., Allen, W. R., & Danley, L. L. (2007). “Assume the position...you fit the description”: Psychosocial experiences and racial battle fatigue among African-American male college students. American Behavioral S , 51 (4), 551–578.

- Smith, W. A., Hung, M., & Franklin, J. D. (2011). Racial battle fatigue and the MisEducation of Black men: Racial microaggressions, societal problems, and environmental stress. Journal of Negro Education , 80 (1), 63–82.

- Takaki, R. (1989). Strangers from a different shore: A history of Asian Americans. Little Brown.

- Teranishi, R. T. (2004). Yellow and brown: Emerging Asian American immigrant populations and residential segregation. Equity & Excellence in Education , 37 (3), 255-263.

- Teranishi, R. T. (2007). Race, ethnicity, and higher education policy: The use of critical quantitative research. New Directions for Institutional Research , 133 , 37-39.

- The Campaign for College Opportunity. (2015). The state of higher education in California: Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders . http://collegecampaign.org/.

- Center for Urban Education. (2020). Laying the groundwork: Concepts and activities for racial equity work. Rossier School of Education, University of Southern California.

- Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive schooling: U.S.-Mexican youth and the politics of caring. State University of New York Press.

- Valle, K. (2016). The progress of Latinos in higher education: Strategies to create student success programs at community colleges. The Association of Community College Trustees.

- Worthington, R. L., Navarro, R. L., Loewy, M., & Hart, J. (2008). Color-blind racial attitudes, social dominance orientation, racial-ethnic group membership and college students’ perceptions of campus climate. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education , 1 (1), 8–19.

- Wright, B., & Tierney, W. G. (1991). American Indians in higher education: A history of cultural conflict. Change, 23 (2), 11-18.